All the mechanics of writing are part of the craft. This is the stuff you can learn to make it so all readers can understand your writing and so your style contributes to the overall experience of your story. This might be the stuff that editors take care of, but editors are not responsible for all of it. Writers are.

Vocab & Diction or Word Choice

Reading a lot of stories and nonfiction content can help improve your vocab and spelling. If you have a real problem with basic words, search online for spelling games or quizzes to take, or peruse a dictionary or "Word of the Day" sites. Understanding prefixes, suffixes, and root words can also help construct words more easily.

Reading a lot of stories and nonfiction content can help improve your vocab and spelling. If you have a real problem with basic words, search online for spelling games or quizzes to take, or peruse a dictionary or "Word of the Day" sites. Understanding prefixes, suffixes, and root words can also help construct words more easily.

Writing is not about using the fanciest word, but if you do pull one out, you need to spell it correctly. Spell check can only go so far. Also, understand the nuances of meaning that some words carry. Some have positive or negative connotations that could make your sentences seem odd if you ignore them.

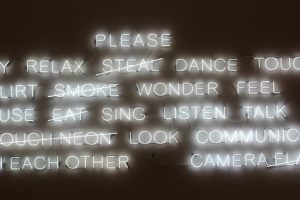

Words are, after all, the material with which we create. If a potter doesn't know clay, she ends up with either a dry brick she can't form or a sloppy mess flinging about the room. We don't want our books to be dry bricks or sloppy messes, right? So we need to know words. Lots of 'em.

Never use a weak word where a stronger word imparts more meaning or feeling. Stronger does not mean longer, more complicated, or existing only in some University linguistics exam but never in common usage.

Never use a weak word where a stronger word imparts more meaning or feeling. Stronger does not mean longer, more complicated, or existing only in some University linguistics exam but never in common usage.

Most writers have seen statements like, "Don't write 'He ran fast.' Instead write, 'He sprinted.'" While this is usually said as part of the "kill adverbs!" non-rule, it is really about being precise and specific. Running fast could also be sprinting, bolting, fleeing, trotting, scampering, rushing, or jogging. These all mean slightly different things. Which is your character REALLY doing?

Adjectives, nouns, and other parts of speech deserve the same level of attention. Your main character may wear a blue shirt, but is it navy blue, robin's egg, denim, or silk? Is he wearing just a shirt or perhaps a button-down, a henley, a ripped t-shirt, or a sweater his grandmother knitted him.

The point is NOT to make your writing longer or fancier. The point is creating a scene that readers can experience right along with the characters.

Example:

Joe ran away from the burning building. His blue shirt was covered with ash.

Joe bolted from the conflagration that claimed the hotel. Ash dulled the sky blue linen of his favorite shirt.

Neither is some masterpiece of literary wonder, but I hope you can see that the second paints a more vivid picture.

Writing Basics

Basic understanding of parts of speech and word usage rules. This also extends to things like past, present, and future tense verbs, adjectives and adverbs and when to use them, and proper capitalization.

Punctuation can change the entire meaning of a sentence. The Oxford comma is famously used as an example in phrases like, "We invited the strippers, JFK and Stalin" vs. "We invited the strippers, JFK, and Stalin." The first sentence means that JFK and Stalin are the strippers. The second sentence means that the strippers, JFK, and Stalin are three separate entities that were invited.

Do I HAVE to know grammar and punctuation? Isn't that the editor's job?

Yes. No.

A plumber needs to know how water flow works in order to lay pipe the right way. A doctor needs to know anatomy and physiology before she can do surgery or prescribe the right medication. A baseball player needs to know how to run fast, swing the bat, and catch a ball before he can play a winning game.

You are a writer. You need to know how to write -- not just tell a good story. Writing requires grammar, punctuation, spelling, word choice, flow, pacing, etc.

Yes, editors absolutely help with this stuff. A good editor is awesome. However, if you do not even make an effort to use your language of choice well, you cannot call yourself a quality writer. I know this sounds judgemental, but I firmly believe it is true. Besides, don't you want to be the best writer you can be? There are no shortcuts.

Once you know and understand the rules, feel free to break them.

Writers have been breaking rules forever. Shakespeare did it. Faulkner did it. So do modern writers.

The ONLY good reason to break grammar, spelling, punctuation, or sentence structure rules, however, is that doing so serves the story. Light touches of dialect in dialogue are great to build characters. Run on sentences spilling over each other in a paragraph create a harried stream-of-consciousness feeling. Lack of punctuation worked for Cormac McCarthy in "The Road."

Does this mean you should throw all the rules out the window and go nuts with experimental literature? Well, you can if you want to. Pushing the boundaries of art has its place in the world. However, if you want marketable fiction, you need to stick with some rules and tweak them to fit your narrative and your characters.

Creativity does not suffer from structure.

Grammar Book

Literary Devices

These are the fancy things like metaphors and alliteration that can either make your fiction writing unique and expressive or bogged down in so much purple prose that your reader may be compelled to stare at a blank wall for an hour or two after reading to give their mind enough time to clear out from all the mess.

There are reasons to use a lot of these things in the story, but, in my opinion, it can be difficult to teach where it should happen and where it should not. Some things like alliteration (Starting many words in a sentence with the same letter sound) or onomatopoeia (Writing out sound words like boom and pop) align more with a whimsical or lighthearted subject matter. Others like foreshadowing, literary irony, and metaphor are frequently used in many different types of stories.

You should develop an ear or eye for it the more you read, learn, and write. If you don't, and you still can't figure out how to use them, you can leave them out and still write a story. They add color, flavor, and emotion to writing, though, and these are important things if you want a really great, can-not-put-it-down type experience for your readers.

Metaphor + Simile -- These compare one thing to another or call one thing another thing. Metaphors are direct comparisons, and similes use "like" or "as."

Imagery -- Using words to create mental images. (This should always exist in writing!)

Foreshadowing + Flashback -- These both play with time. Foreshadowing gives hints about what is to come. Flashbacks are when characters are mentally transported back in time to remember or re-experience some event.

Symbolism -- The use of an object or idea that has deeper or alternative meanings than the regular one.

Analogy -- Creating a link or comparison between two objects or topics to increase understanding.

Verbal Irony -- Expressing something to mean the opposite of what it really means.

Situational Irony -- Something happens that is opposite of the expected. This can also be when one character knows something and the other one doesn't and is surprised.

Author Intrusion -- The writer interjects something in the story from their point of view. This is generally frowned upon, but might be used for certain effects.

Deus Ex Machina -- "God in the Machine." Mark of a weak plot. It means that something happens to "save the day!" in some unrealistic and too-easy fashion.

Allusions -- Making a reference to something in the realm of common knowledge.

Alliteration -- Words starting with the same letter or sound.

Assonance -- Words with the same vowel sounds grouped closely.

Consonance -- Repetitive use of consonants, but not necessarily at the start of the word.

Onomatopoeia -- "Boom!" "Pop!" Using words that sound like what they mean. This is usually only done in comic or children's books or similarily whimsical stories.

Rhyme -- Words that end with the same sounds.

Hyperbole -- Over-stating or exaggerating something to increase meaning or emotion.

Juxtaposition -- Present parallel concepts, characters, or thoughts to make their differences or similarities more prominent.

Paradox -- When contradictory ideas or concepts reveal a deeper meaning when used together.

Personification -- Giving human characteristics to non-human beings or objects.

Verisimilitude -- Implying and providing backup narrative in order to make it appear to be true or real even if it's not.